I just had the great fortune to climb with one of my best friends, the incredible Bailey White (she/they), who visited me in the Red River Gorge for a few days in early November. Bailey is a recent graduate from Princeton University’s EEB (ecology and evolutionary ecology) department, a talented wildlife and sports photographer, and a rock climber of many years. I’ve had the privilege to overhear her teach many a belay class, have watched her insightful short films with wonder and joy, and have had countless discussions with her on modern-world ethics.

There’s much to admire about Bailey. Perhaps one of her most inspiring qualities, though, is her determination to have a good life—not in spite of major depressive disorder (MDD), but in harmony with it.

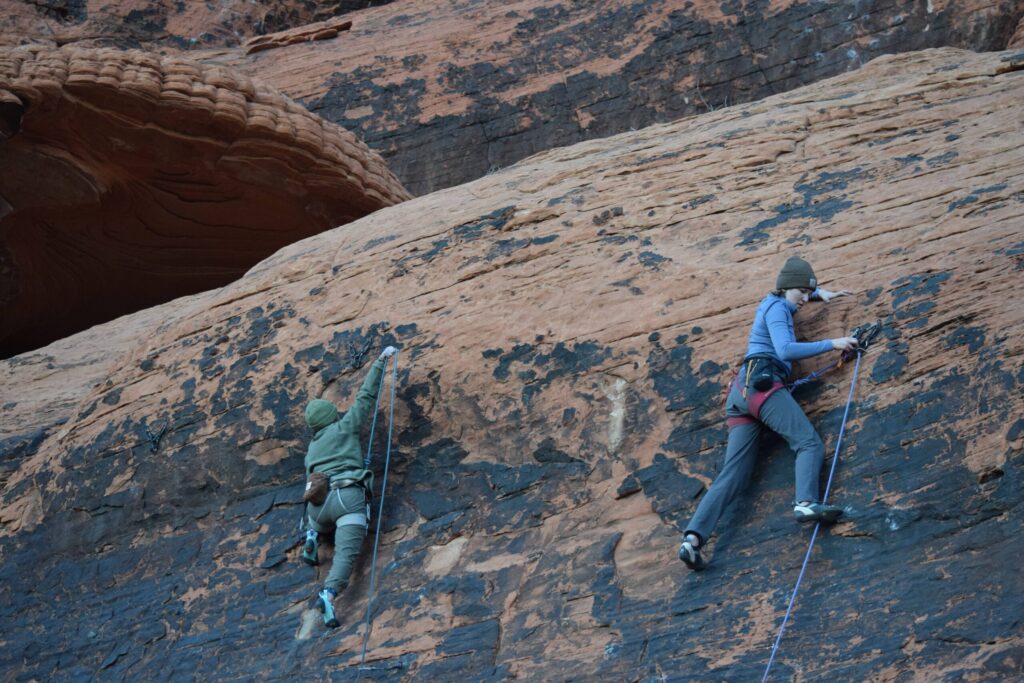

Me and Bailey, belaying side-by-side at Cactus Massacre in Red Rock Canyon

I called Bailey after her trip out to the Red River Gorge to capture any thoughts she might want to share with the River Gorge Guild. As a climber who deals with MDD myself, I had lots of questions for Bailey about living with mental illness and how it impacts her life as a climber. Bailey had just as much to say in reply on the matter. After speaking with Bailey, though, I found that our conversation could be boiled down into three main points that came up over and over again.

- There’s no such thing as “should.”

- Talk to yourself the way you would talk to a friend, and believe that your friends really mean the nice things that they say to you.

- When you feel bad, just do the thing anyway.

All (but one) of the photos in this article were taken either of or by Bailey White!

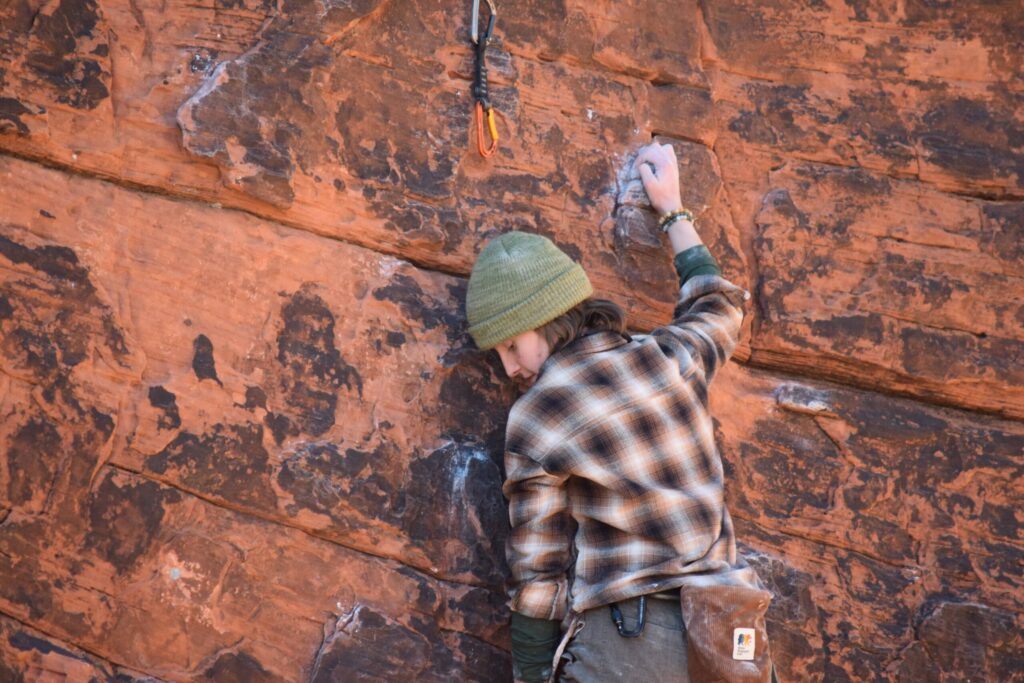

Bailey at Secret Garden in Miller Fork

1.

At many points in our conversation, Bailey called “should” a “terrible word.” The word cropped up countless times, often seemingly against her will, especially when describing how she felt her own ability stacked up against her expectations. The first time she used the word “should” was when describing how the trip went.

As Bailey told me, she came down to the Red and “intentionally had a lot of fun,” making an effort to live in the present and treat the adventure more like play than work. What she described as the only truly bad moment, though, was when she hopped on the last cool-down climb of the trip and found it to be harder than expected.

Me clipping on Brown-Eyed Girl, as shot by Bailey

At first, Bailey described it as a climb that she “should” have been able to complete without struggling, but she quickly interrupted herself to clarify the language. This was when she told me that “should is such a terrible word,” acknowledging that “I am very aware that you can’t be climbing at your peak every single day–that’s just not how it works. That’s not how sports work.” Having harsh, grade-related expectations can cause a single instance of struggle to generate a negative sense of self. Bailey tries to avoid that mindset, even if it can be difficult.

“It made me kind of, like, doubt my abilities and my achievements of the two previous days,” Bailey confessed regarding that tough cool-down climb, “[but] it was just a momentary setback.”

“Should” came up again when we were discussing Bailey’s winter training plans, in which she attempted to avoid the word when explaining why she wants to make it to the climbing gym more often. She leaned into the benefits of personal growth and feeling physically stronger rather than emphasizing obligation. Making it out to the climbing gym even when you’re having a bad day, Bailey explained to me, allows you to enjoy your good days even more.

As we got deeper into our conversation, Bailey revealed that this sense of “should” and chasing stiff grades are actually much less important to her than some other kinds of success one can find in climbing. “The point of climbing [for some people] is not to climb the hardest climb possible,” she explained; “it’s to get some other intrinsic benefits.” Some of the most important “intrinsic benefits” to Bailey are being able to move with ease; feeling in touch with her body; feeling confident and natural on the wall; and other sensations of the sort.

“The longer I climb, the more I realize that yes, grades matter,” Bailey explained, “but for me, my accomplishment after finishing a climb has less to do with how hard I think the climb was and [more with] how well I climbed it.”

Bailey on a sweeeet send of Brown-Eyed Girl, which they told me was one of their favorite climbs of the trip–not because of the grade, but because they felt that they truly climbed it well

Here, Bailey lights a path to replacing “should” with other, gentler reasons to get on the wall. Not all of us climb to prove that we can do the things we “should” be able to do–we climb for the joy of movement, to spend time outside, to be with friends, and for countless other reasons unrelated to our objective ability. We climb to feel good.

Bailey, repping Miguel’s Pizza at Cactus Massacre

2.

Bailey and I also talked a lot about inner and outer dialogue. She discussed two main ways in which these kinds of dialogue can take harmful turns for depressed climbers (or at least for her): when you speak to yourself unkindly, and when you struggle to accept the kind words of others.

The first of these is closely tied to “should.” As Bailey describes, she often has her best days when her expectations of her climbing abilities line up with reality: she feels just as strong as she expects, she’s able to cruise her onsight grades comfortably, her body feels ready to move, and so on. Just like all of us, though, Bailey says that it’s really unusual for every day to feel like this. What’s hard about being depressed is that Bailey (and so many others of us, MDD or not), can find it difficult to detach these bad days from over-arching self-worth.

If a friend is having similarly a bad day, Bailey explained, “I wouldn’t think that they’re wasting their time or that they’re not good.” It can be difficult to have the same level of compassion for yourself. “And that makes me really stressed,” Bailey confessed. “Why can’t I be nice to myself?”

Amazing flic that Bailey captured of me hesitating just before the clip in Red Rock Canyon

The difference between what Bailey might say to a friend versus what she says to herself creates what she calls an “internal ethical disharmony,” upsetting her in two ways. Firstly–it never feels good to receive negative feedback, even if (perhaps especially if) it’s coming from yourself. Secondly, it further upsets her to know that she, as someone who values kindness, can struggle to be kind in certain situations (namely, when she’s required to be kind to herself).

In board climbing, as Bailey pointed out in our interview, these internal and external dialogues are particularly loud. Bailey and I spent some time talking about the culture of board climbing, both Kilter and Moon, and how an intense try-hard training culture has developed around these sorts of walls. This culture can make it emotionally complicated to crack into the space if you’re just getting started.

As Bailey explained to me, the difficulty of accessing these complex spaces is not just due to more obvious external factors and dialogues, but some internal ones, too. Even when all of the external factors are just right, it still can be difficult to accept that you are where you’re meant to be.

If you haven’t seen one before–Kilterboards and Moonboards are both small and super-steep walls that can be used to train climbing overhang on less-than-good holds

Board culture (and training culture in general) can be prohibitive. “It’s like, if you’re not sending this grade or climbing this hard, you, know, whatever,” Bailey told me, “if you don’t have perfect mental game…it feels like you’re not good enough to be in that space.” She further acknowledged, though, that “that doesn’t mean I don’t belong there.”

Whatever external forces might be putting pressure on climbers entering the training space, Bailey emphasizes the importance of not attaching subjective meaning to certain objective facts. Board climbing “less strongly” than a given person doesn’t mean that you have any less a right to be there than they do.

Bailey cruising the slabby, weird, and wonderful “Little Wing“

Both Bailey and I agreed that separating facts from subjective meaning can be difficult for people like us—even when others try to help us do so.

In our conversation about Moonboarding, Bailey expressed her gratitude for a dear friend of hers who we’ll call D.

Bailey regards D both as a very strong climber and very strong of character. When they Moonboard together, D always celebrates her successes alongside his own and emphasizes that she is just as welcome in the training space as he is. Bailey acknowledged her excellent luck to be able to climb with such a welcoming friend, but further pointed out that this fortunate circumstance is only half the battle.

“There’s also an added hurdle, like, within me,” Bailey described, “where I need to accept that he’s being genuine.” This task might be more difficult for some than it sounds to others, and it can take constant work to overcome.

Bailey, stanced up

There’s an intersection in this issue where action can be taken. If you find yourself comfortably inhabiting a space that is sometimes prohibitive, like the mats under a Moonboard, you can take steps to be extra welcoming to your peers. Know that entering these spaces is easy for some people and almost impossible for others, and take this knowledge into account when you decide how to behave. Just as we can empathetically extend understanding to climbers who are physically different from us, we can also do so with climbers who might mentally be different from us.

If you find yourself hesitating to enter one such prohibitive space or feeling uncomfortable while already in one, you can consciously practice accepting kind words from yourself and from others, one day at a time.

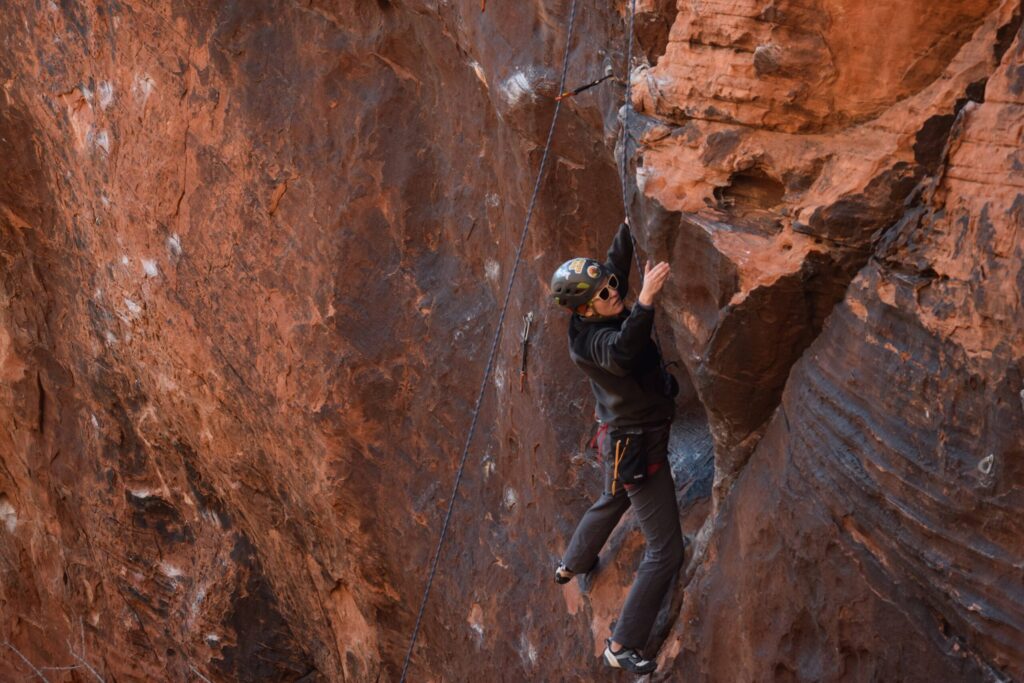

Bailey, almost at the anchors somewhere in Red Rock Canyon

3.

Bailey and I concluded our conversation by chatting about motivation. As our readers may or may not know, rallying motivation can be one of the most difficult tasks for a person with MDD. And as (I quote) “also an ADHD-having person,” Bailey observed that it can be extra burdensome for her to gather motivation into momentum, even to do the things she loves most.

“Sometimes that means I don’t go to the gym for two or three weeks,” Bailey admitted. Of course, skipping the gym is not an intrinsically bad thing—every climber can go to the climbing gym as often or as sparsely as they so choose. However, Bailey also pointed out that going to the gym makes her feel good, she likes to go, and she usually wants to go—it just can be so difficult to decide to do it in the first place.

Bailey lookin’ cool at a rest stop somewhere between Las Vegas and Salt Lake City

“I struggle to do things when the conditions don’t feel perfect,” Bailey explained, then adding that “[sometimes I] use my mental health as an excuse not to go.” Mimicking her internal dialogue, she further said, “I’m just gonna feel more depressed and it’s gonna be a waste of time.” Even if just doing-the-thing might make Bailey feel better at the end of the day, knowing that fact doesn’t make it any easier to flint the initial spark.

What does Bailey plan to do about this, then, in order to make her winter training as fulfilling, productive, and nourishing as she can under her circumstances?

When I asked, Bailey provided me with a piece of advice from a friend. This friend, Bailey informed me, lives with anxiety. Instead of attempting to suppress her anxious thoughts, though, this friend instead works hard to have the life she wants anyway, even if she’s not feeling perfectly well when she sets out to do so. Then, quoting her own state of mind, Bailey laid one of my favorite lines of the interview on me:

“I don’t feel good and that’s ok. I can climb and not feel good and that’s fine.”

Bailey making their way out of the absolutely massive dish on “Pain Relief” (I can’t remember who was holding the camera for this one)

As a climber with MDD myself, I can confirm that a bad mental day can easily deter me from climbing or otherwise doing things that I want to do. Bailey’s proffered solution is to, rather than working on always feeling good before you set out for the day, work on setting out regardless of how you feel. Focusing on the former can set unrealistic standards for your emotional states and prevent you from engaging with the parts of life that you love most.

When you hit the upswing of your sad spell, Bailey described, you then can come to the climbing gym “a little bit stronger because you went out that day” instead of waiting to feel good before you step out the front door at all.

Of course, all of this is a long, difficult process that is easier described than enacted. “There are going to be days, weeks, or even months where I’m feeling very unmotivated,” Bailey told me candidly, but she’s “trying to be better every single day.” She’s borrowing the theme for her winter training from a show she’s been watching called The Bear: “the only way to break a habit is to break a habit.”

As a depressed person, it can be easy to fall into routines that are more comfortable than they are beneficial. At the very beginning of our interview, Bailey described the trip to the Red River Gorge as a welcome interjection in a daily pattern that was becoming monotonous. That shake-up provided a rare opportunity.

“I’m really proud of myself because this morning I woke up naturally at like 6:45,” Bailey told me. “I got up. I fed Winston (their cat). Then I had a moment where I was like…okay. I have a choice before me. I can go back to sleep and sleep for three more hours, which feels so comfortable right now…or, I’m up. I can get dressed so that I can go to the gym right now. And I’m really proud of myself because I decided to go to the gym.”

And sometimes all it takes is one decision.

Bailey in their element, crushing a gym day in Salt Lake City

“This morning was just one little step,” Bailey continued. “I was like, okay, I can see the choice and I’m going to very intentionally take the choice that’s in line with my goals. I did it, and I had a great session…it was so fun. That makes me very excited to wake up tomorrow morning and then see that same choice.”

Of course, it’s not required to make this same decision every single morning, nor is it a reasonable expectation, given the limits that one’s body, mental health, and life schedule place on their training. However, making the decision to show up just once is a bigger step than Bailey gave themselves credit for. Just one step can show you what’s possible, even on the days that you’re feeling bad.

Leave a Reply